Articles

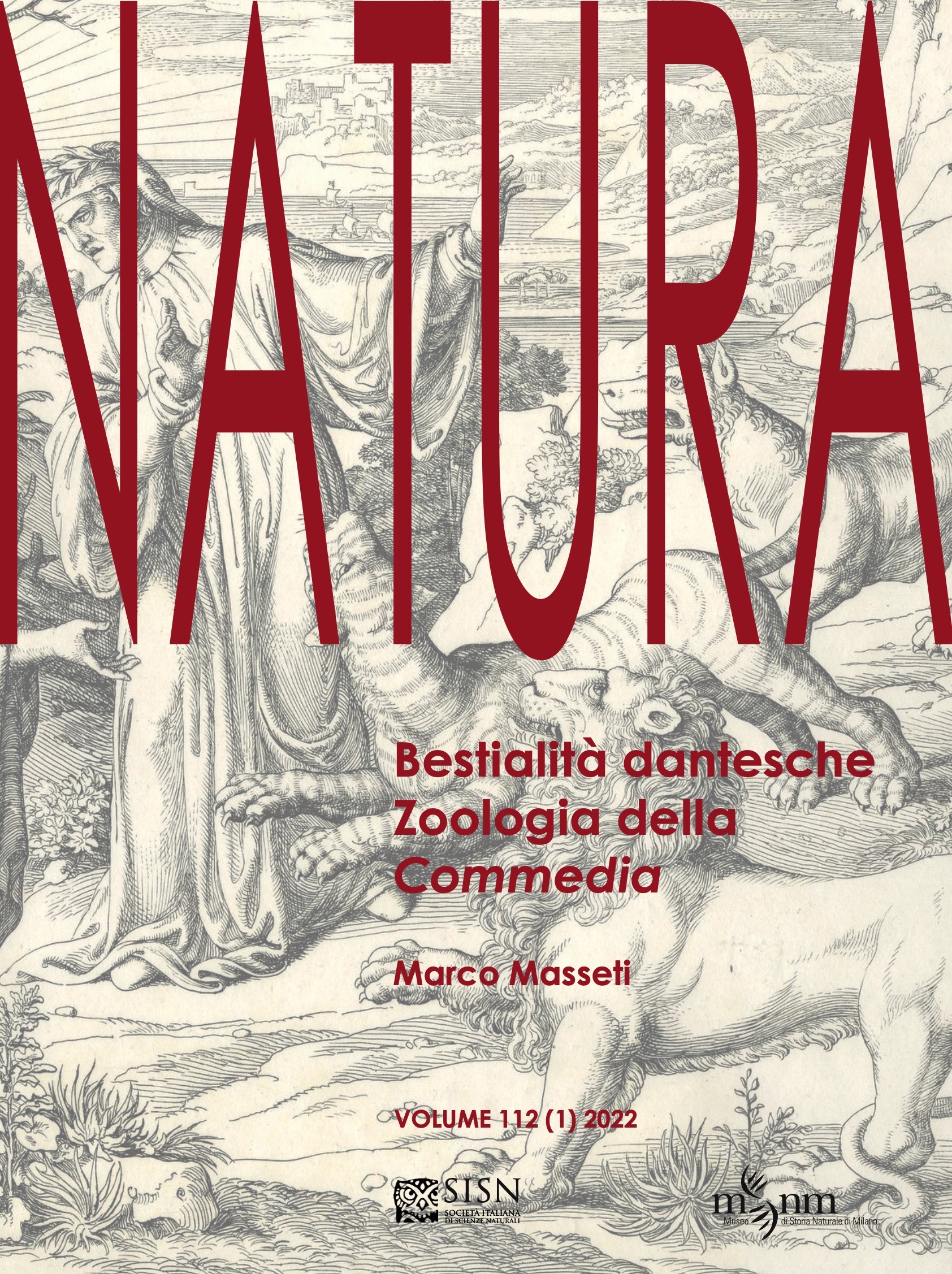

Vol. 112 No. 1 (2022)

Dante's bestialities. Zoology of the Commedia

Flies, mosquitoes, fireflies and... Lions. Preface by Domenico De Martino

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Published: 31 October 2024

544

Views

105

Downloads